Vn-Z.vn November 18, 2023, In science fiction films, filmmakers have built mystical worlds. Including the world of Vampires, in this mysterious world the vampire virus appears as a threat. These are not just ordinary viruses, but they have the ability to mutate and invade the human body, turning virus-infected people into "vampires" with supernatural powers.

In the world of science fiction, in reality scientists have discovered a virus capable of hunting other viruses to serve the replication process. This virus may hold the key to new antiviral therapies

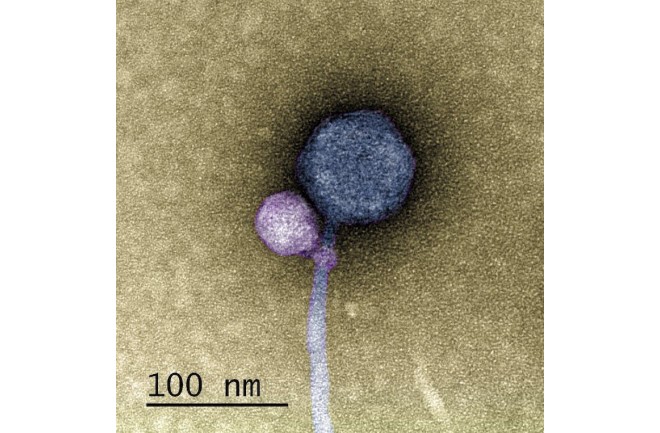

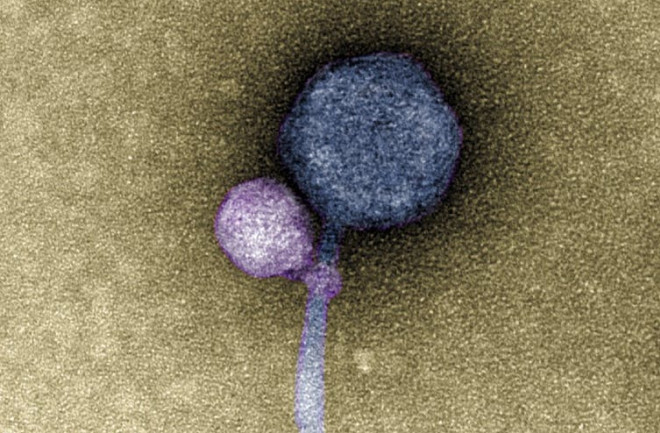

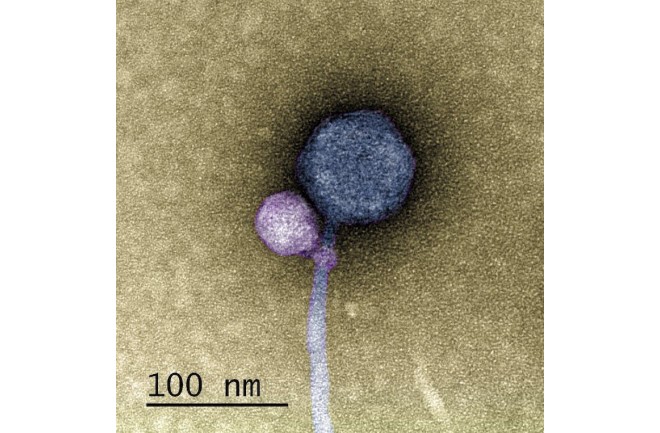

The image above shows the bacterium Streptomyces satellite phage MiniFlayer (purple) attached to the neck of its helper virus, Streptomyces phage MindFlayer (gray). (Author: Tagide deCarvalho, CC BY-SA)

Recently, the world has experienced dangerous flu pandemics caused by viruses such as H5N1 and COVID. Have you ever wondered whether the viruses that created these dangerous flu pandemics can also cause the flu themselves? The answer is yes, viruses can actually cause disease. Even the ultimate culprits are other viruses.

Viruses can be pathogenic in the sense that their normal function is affected. When a virus enters a cell, it can go into a dormant state or begin replicating immediately. When replicating, the virus actually takes control of the cell's molecular "factory" to make lots of copies of itself, then exits the cell to release new copies.

Sometimes, a virus enters a cell only to discover that its new temporary home is already home to another dormant virus. Surprising, right? What follows is a war for cell control, which can be won by either side in this contest.

But sometimes, viruses that enter a cell have a special surprise waiting for them. Inside the cell, viral parasites are waiting to prey on incoming viruses.

Scientists studying virus evolution recently discovered a virus that is embedded in the neck of another virus. This action of clinging to the neck reminds us of the way vampires do in science fiction movies. Vampire Virus! (Vampire viruses)

Biologists have known for decades about the existence of viruses that prey on other viruses, called "viral satellites." In 1973, scientists studying bacteriophage P2, a virus that infects the intestinal bacterium Escherichia coli, discovered that this infection sometimes resulted in two different viruses arising. from cells: phage P2 and phage P4.

Bacteriophage P4 is a thermophilic virus, which means it can integrate into the host cell's plasmodesma and enter a dormant state. When P2 infects a cell that already contains P4, the latent P4 quickly awakens and uses P2's genetic instructions to create hundreds of small virus particles of its own. P2 is without a doubt lucky if it can replicate a few times. In this case, biologists call P2 a "helper virus," because the P4 satellite needs P2's genetic material to replicate and spread.

Subsequent studies have shown that most bacterial species have a diverse system of helper satellite-viruses, similar to the P4-P2 system. However, viral satellites are not limited to bacteria. Soon after the largest known virus, mimivirus, was discovered in 2003, scientists also discovered its satellite, named Sputnik. Plant virus satellites that lurk in plant cells waiting for other viruses are also common and can have important impacts on agricultural products.

www.nature.com

www.nature.com

Although researchers have found helper virus-satellite systems in nearly every domain of life, their important role in biology remains underappreciated. Most obviously, viral satellites directly influence their "helper" viruses, often harming them but sometimes making them more effective killers. However, this is probably only a small part of their contribution to biology.

Both satellites and helper viruses are engaged in a constant evolutionary race. Satellites evolve new ways to take advantage of helper viruses, and helper viruses evolve preventative measures to stop them. Because both sides are viruses, the outcome of this internal war includes something meaningful to humans: research into anti-viral drugs.

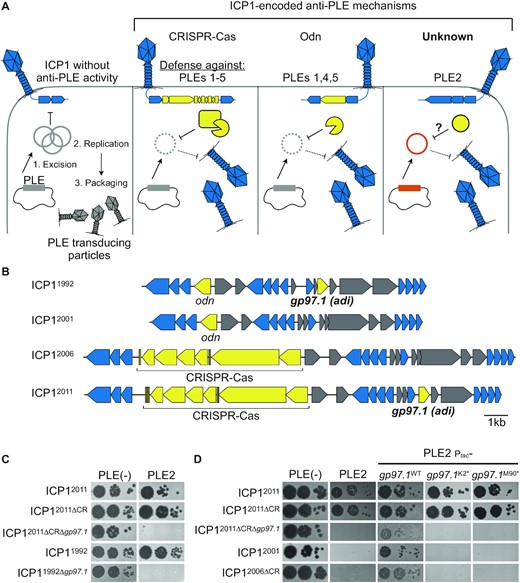

Recently many anti-virus systems are thought to have evolved in bacteria, such as the CRISPR-Cas9 molecular scissors used in gene editing, which may have come from bacterial phages and their satellites. Ironically, given their high reproductive and mutation rates, helper viruses and their satellites have become evolutionary hotspots for antiviral weapons. Trying to outwit each other, satellites and helper viruses have created a series of unique anti-virus systems, which researchers can take advantage of.

Viral satellites have the potential to change the way researchers understand anti-virus strategies, but there is still a lot to be learned about them. Scientists have described a satellite phage bacterium that is completely different from known satellites, one that has evolved a unique, mysterious lifestyle.

This image shows the satellite phage Streptomyces MiniFlayer (purple) attached to the neck of its helper virus, the phage Streptomyces MindFlayer (gray). (Source: Tagide deCarvalho, CC BY-SA)

First-year students at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County isolated a satellite phage bacteria called MiniFlayer from the soil bacterium Streptomyces scabiei. MiniFlayer was found to be closely related to a helper virus called the MindFlayer phage that infects Streptomyces bacteria. However, subsequent studies have discovered that MiniFlayer is no ordinary satellite virus.

MiniFlayer is the first known satellite phage bacterium that has lost its ability to lie dormant. The inability to camouflage and wait for helper viruses to enter cells poses an important challenge for satellite phage bacteria. If one needs another virus to replicate, how can one ensure that it will enter the cell at about the same time?

MiniFlayer has solved this challenge with sophistication and creativity like something out of a horror movie. Instead of waiting in disguise, MiniFlayer switched to attack tactics. Inspired by both "Dracula" and "Alien," this satellite phage has evolved a short connector that allows it to latch onto the helper virus's neck like a vampire, searching for them together. a new "host". We don't yet know how MiniFlayer suppresses its helper virus, or whether MindFlayer has evolved preventative measures.

If the recent pandemic has taught us anything, it's that our supply of antiviral drugs is quite limited. Research into the complexity, intersectionality and sometimes attackiness of viruses and their satellites, such as the ability of the MiniFlayer to attach to the neck of a helper virus, has the potential to open new doors for research into whether anti-viral treatment.

Vn-Z.vn team compiled

In the world of science fiction, in reality scientists have discovered a virus capable of hunting other viruses to serve the replication process. This virus may hold the key to new antiviral therapies

The image above shows the bacterium Streptomyces satellite phage MiniFlayer (purple) attached to the neck of its helper virus, Streptomyces phage MindFlayer (gray). (Author: Tagide deCarvalho, CC BY-SA)

Recently, the world has experienced dangerous flu pandemics caused by viruses such as H5N1 and COVID. Have you ever wondered whether the viruses that created these dangerous flu pandemics can also cause the flu themselves? The answer is yes, viruses can actually cause disease. Even the ultimate culprits are other viruses.

Viruses can be pathogenic in the sense that their normal function is affected. When a virus enters a cell, it can go into a dormant state or begin replicating immediately. When replicating, the virus actually takes control of the cell's molecular "factory" to make lots of copies of itself, then exits the cell to release new copies.

Sometimes, a virus enters a cell only to discover that its new temporary home is already home to another dormant virus. Surprising, right? What follows is a war for cell control, which can be won by either side in this contest.

But sometimes, viruses that enter a cell have a special surprise waiting for them. Inside the cell, viral parasites are waiting to prey on incoming viruses.

Scientists studying virus evolution recently discovered a virus that is embedded in the neck of another virus. This action of clinging to the neck reminds us of the way vampires do in science fiction movies. Vampire Virus! (Vampire viruses)

Biologists have known for decades about the existence of viruses that prey on other viruses, called "viral satellites." In 1973, scientists studying bacteriophage P2, a virus that infects the intestinal bacterium Escherichia coli, discovered that this infection sometimes resulted in two different viruses arising. from cells: phage P2 and phage P4.

Bacteriophage P4 is a thermophilic virus, which means it can integrate into the host cell's plasmodesma and enter a dormant state. When P2 infects a cell that already contains P4, the latent P4 quickly awakens and uses P2's genetic instructions to create hundreds of small virus particles of its own. P2 is without a doubt lucky if it can replicate a few times. In this case, biologists call P2 a "helper virus," because the P4 satellite needs P2's genetic material to replicate and spread.

Subsequent studies have shown that most bacterial species have a diverse system of helper satellite-viruses, similar to the P4-P2 system. However, viral satellites are not limited to bacteria. Soon after the largest known virus, mimivirus, was discovered in 2003, scientists also discovered its satellite, named Sputnik. Plant virus satellites that lurk in plant cells waiting for other viruses are also common and can have important impacts on agricultural products.

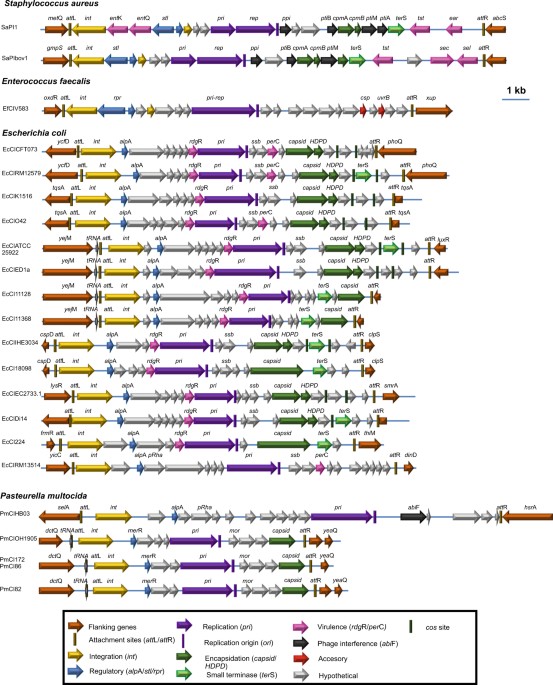

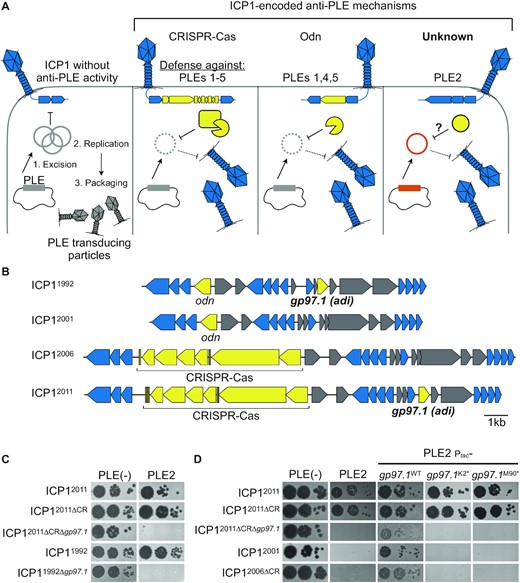

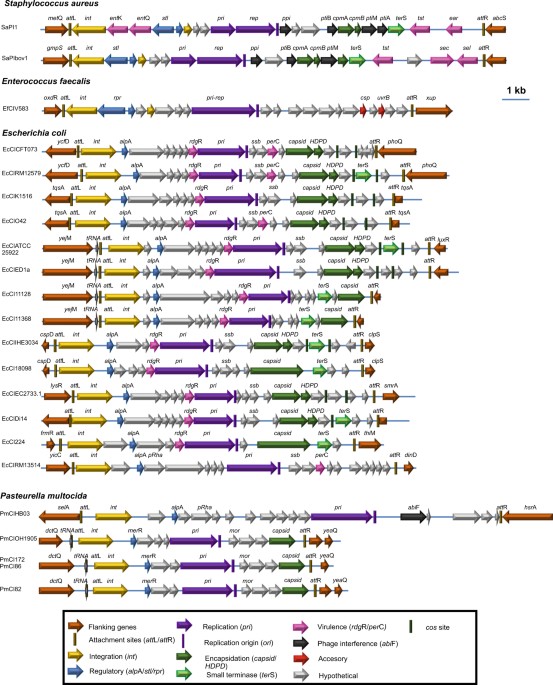

Phage-inducible chromosomal islands are ubiquitous within the bacterial universe - The ISME Journal

Phage-inducible chromosomal islands (PICIs) are a recently discovered family of pathogenicity islands that contribute substantively to horizontal gene transfer, host adaptation and virulence in Gram-positive cocci. Here we report that similar elements also occur widely in Gram-negative bacteria...

Although researchers have found helper virus-satellite systems in nearly every domain of life, their important role in biology remains underappreciated. Most obviously, viral satellites directly influence their "helper" viruses, often harming them but sometimes making them more effective killers. However, this is probably only a small part of their contribution to biology.

Both satellites and helper viruses are engaged in a constant evolutionary race. Satellites evolve new ways to take advantage of helper viruses, and helper viruses evolve preventative measures to stop them. Because both sides are viruses, the outcome of this internal war includes something meaningful to humans: research into anti-viral drugs.

Recently many anti-virus systems are thought to have evolved in bacteria, such as the CRISPR-Cas9 molecular scissors used in gene editing, which may have come from bacterial phages and their satellites. Ironically, given their high reproductive and mutation rates, helper viruses and their satellites have become evolutionary hotspots for antiviral weapons. Trying to outwit each other, satellites and helper viruses have created a series of unique anti-virus systems, which researchers can take advantage of.

Viral satellites have the potential to change the way researchers understand anti-virus strategies, but there is still a lot to be learned about them. Scientists have described a satellite phage bacterium that is completely different from known satellites, one that has evolved a unique, mysterious lifestyle.

This image shows the satellite phage Streptomyces MiniFlayer (purple) attached to the neck of its helper virus, the phage Streptomyces MindFlayer (gray). (Source: Tagide deCarvalho, CC BY-SA)

First-year students at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County isolated a satellite phage bacteria called MiniFlayer from the soil bacterium Streptomyces scabiei. MiniFlayer was found to be closely related to a helper virus called the MindFlayer phage that infects Streptomyces bacteria. However, subsequent studies have discovered that MiniFlayer is no ordinary satellite virus.

MiniFlayer is the first known satellite phage bacterium that has lost its ability to lie dormant. The inability to camouflage and wait for helper viruses to enter cells poses an important challenge for satellite phage bacteria. If one needs another virus to replicate, how can one ensure that it will enter the cell at about the same time?

MiniFlayer has solved this challenge with sophistication and creativity like something out of a horror movie. Instead of waiting in disguise, MiniFlayer switched to attack tactics. Inspired by both "Dracula" and "Alien," this satellite phage has evolved a short connector that allows it to latch onto the helper virus's neck like a vampire, searching for them together. a new "host". We don't yet know how MiniFlayer suppresses its helper virus, or whether MindFlayer has evolved preventative measures.

If the recent pandemic has taught us anything, it's that our supply of antiviral drugs is quite limited. Research into the complexity, intersectionality and sometimes attackiness of viruses and their satellites, such as the ability of the MiniFlayer to attach to the neck of a helper virus, has the potential to open new doors for research into whether anti-viral treatment.

Vn-Z.vn team compiled